Editor’s Note: This report includes a graphic image and details of violence.

Hundreds of families gathered in the West Darfur capital of El Geneina on June 15, plotting their escape from what had become a hellscape of blown-out buildings scrawled with racist graffiti and streets strewn with corpses. The state governor had just been executed and mutilated by Arab militia groups, leaving civilians with no choice but to flee.

In the early hours of that morning, residents set off en masse from southern El Geneina, many trying to reach the nearby Sudanese military headquarters where they thought they might find safety. But they said they were quickly thwarted by RSF attacks. Some were summarily executed in the streets, survivors said. Others died in a mass drowning incident, shot at as they attempted to cross a river. Many of those who managed to make it out were ambushed near the border with Chad, forced to sit in the sand before being told to run to safety as they were sprayed with bullets.

“June 15, 16 and 17 were the bloodiest days in Geneina,” said the humanitarian worker, who was part of a city-wide network of aid workers collecting bodies from the streets, and based the death toll on information gathered by the group. “June 15 was the worst of them all,” he added.

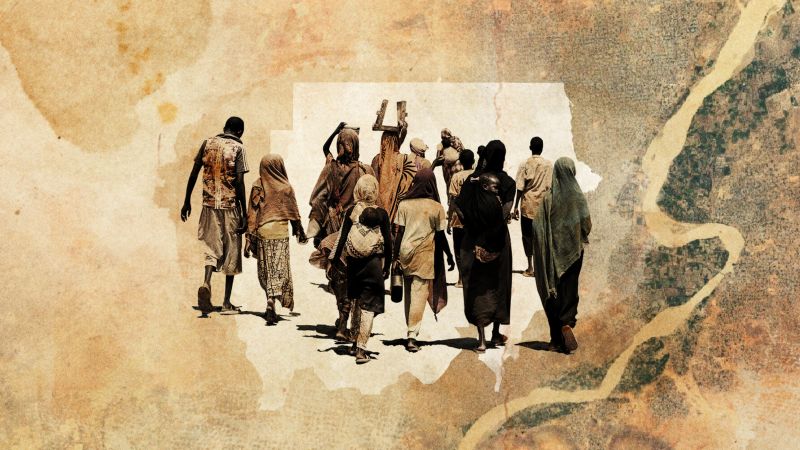

Conflict erupted between the RSF and the Sudanese army in April. Since then, more than one million people have fled to neighboring countries, according to estimates from the International Organization for Migration.

A video shared on Twitter on June 14, 2023, showing hundreds of refugees from El Geneina walking towards Chad.

“To say you were Masalit was a death sentence,” said Jamal Khamiss, a human rights lawyer, referring to his non-Arab tribe, one of the biggest in Darfur. Khamiss was among those who said that they fled from El Geneina to Chad, surviving a series of RSF and allied militia positions by concealing his ethnicity.

He said he only managed to escape execution because he convinced the fighters that he belonged to the Tagoy ethnic group, whose language he speaks proficiently.

Khamiss recalled an 8-year-old boy grabbing his hand, part of the group walking towards the Chadian border, rushing to put distance between themselves and the violence.

“When we arrived at Shukri, they captured us,” said Khamiss. “They told us to run away. They shot and killed the 8-year-old boy. He was trying to run away, and they shot him in the head.

“June 15 was one of the worst days in all of Darfur’s history.”

Reviving a genocidal playbook

Darfur has been ravaged by a decades-long ethnic cleansing campaign that peaked in the early 2000s, and was spearheaded by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo — widely known as Hemedti. Then a leader of the Janjaweed militia, Hemedti, now commander of the RSF, appears to have revived those tactics in a nationwide struggle to wrest control of Sudan from the country’s military.

Before Sudan’s current war erupted Hemedti was the second most powerful person in Sudan’s government. He allied with his now bitter enemy, Sudan’s military leader Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, to stifle a democratic movement that helped overthrow then dictator Omar al-Bashir, later leading a coup together against an internationally recognized transitional government.

When their rivalry flared into open warfare, Darfur emerged as a flashpoint in the conflict. Hemedti redoubled his efforts to consolidate control over the restive region, taking over key border crossings that helped him bolster his arms supplies from external players such as Russian mercenary group Wagner, and unleashing a brutal assault on local tribes that has exacted a huge death toll.

Weeks after conflict first erupted in Sudan, community activists in Darfur warned that the RSF and allied militia had turbocharged violence in the region, torching large swathes of land in villages and whole neighborhoods, arbitrarily killing civilians and raping women.

El Geneina is the largest Sudanese city to fall to the RSF and its precursor, the Janjaweed. For weeks, armed locals fought against the RSF and its allies as the city came under sustained attacks, and shelling.

The United Nations raised the alarm in June over ethnic targeting and killing of people from the Masalit community in El Geneina, after reports of summary executions and “persistent hate speech,” including calls to kill or expel them.

The vast majority of those who managed to make it out of El Geneina alive sought refuge in the Chadian border town of Adre, about 22 miles (35 kilometers) away from the city.

On June 15, the town received the highest number of migrants in a single day, along with the highest number of casualties — 261 — since the Sudan conflict broke out, according to Doctors Without Borders, widely known by its French name, Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), which runs the only hospital in Adre. The number of wounded people that arrived at the hospital was even higher the next day: 387.

“There were MSF vehicles dropping patients off … there were Chadian army vehicles bringing in patients. Chadian police bringing in patients … there were carts pulled by men bringing in patients,” he said.

Most of the wounds he treated indicated people were shot while fleeing, Maloba said — gunshot wounds to the back, legs and buttocks. Many of those injured were women and children.

“I remember the first death I recorded,” said Maloba, recounting the afternoon of June 15. “It was a 2-year-old who had been shot several times in the abdomen.”

Between June 15 and 18, 112 women were treated at the MSF hospital for gunshot wounds and injuries from beatings and other assaults. Half of them were pregnant.

El Geneina first became embroiled in the current Sudan conflict in late April. RSF forces and their allies repeatedly shelled the city, according to eyewitnesses and community-based organizations, leading to hundreds of deaths in the first months of the violence.

The fighting intensified in early June, culminating in the execution of West Darfur governor Khamis Abbakar on June 14. After his death, video footage emerged showing Abbakar being taken into custody by RSF fighters. The Sudanese military blamed the RSF for his killing, a charge which the RSF denies.

‘Shot as they drowned’

The group of fleeing families was almost immediately ambushed after they embarked on their escape in the early hours of June 15, eyewitnesses said. The first major incident occurred in front of the El Geneina Teaching Hospital, near the center of the city. “The fighters had DShK’s (Soviet-era heavy machine guns) and other heavy weaponry,” said Khamiss, the lawyer from El Geneina.

But the river was running higher than usual that day, according to eyewitnesses, and corroborated by satellite imagery, leading scores of people unable to swim to drown. Three eyewitnesses at Wadi Kaja said militia forces shot at people in the water, including children and elderly people, as they desperately attempted to swim across.

Sudanese Red Crescent collects the bodies

A propaganda video shared by the RSF on its official YouTube channel on July 2 further corroborated allegations of the massacres carried out in El Geneina.

The footage showed RSF West Darfur commander General Abdelrahman Juma — who also appeared in the West Darfur governor’s abduction video — overseeing a “clean-up” operation in the city.

Juma is seen in the video thanking members of the Sudanese Red Crescent Society (SRC) for their help. The SRC is the International Committee of the Red Cross’ primary partner on the ground in Sudan, and the ICRC has said its personnel have been assisting with humanitarian aid distribution and collecting bodies since the conflict started.

In a press conference on Saturday, West Darfur official Mujeeb Rahman Muhammad Rezk said that 30 mass graves had been discovered in and around West Darfur, including in Wadi Kaja, where the RSF and its allies dumped bodies. He said the RSF forced the SRC “to prepare the bodies, wrap, and tie them up in tarpaulins for burial … When they proceeded to burying the bodies, they were threatened by militias and forced to leave, so that the militias could bury the bodies in unidentified locations.”

A propaganda video shared by the RSF showing its West Darfur commander General Abdelrahman Juma and SRC members in El Geneina.

The ICRC says that confidentiality is key to maintaining its neutrality in times of conflict and preserving access to hard-hit areas. However, it also states that it reserves the right to speak out in “exceptional cases” where violations are “major and repeated or likely to be repeated” and where “our staff must have witnessed the violations with their own eyes, or at least have the information from reliable and verifiable sources.”

The ICRC also said it may in some cases “share concerns with selected third parties,” such as other states or international bodies, with a view toward influencing those involved in armed conflicts.

The SRC in El Geneina declined to comment on whether it had informed the ICRC of the bodies collected in the city.

Summary executions near the border with Chad

The escape from El Geneina became even more perilous after the families made it out of the city, according to survivors, with the path to the Chadian border peppered with RSF and allied militia positions.

Two body collectors from El Geneina said that the crowd was ambushed at four or five different locations on a roughly 7-kilometer (4-mile) stretch of road between the city and Shukri, near the border with Chad.

One man, who asked not to be named, said he had lost eight members of his family in that area where Arab militias reportedly have a base. The MSF and the UN have also reported this location as a site of summary executions.

“They were executed. They were moving together just before Shukri and they were shot from behind,” he said. Among the dead were his father and uncle, who he said were shot at point-blank range in the head.

“My grandmother was with them. She saw two of her sons being killed before her eyes,” he said.

A day after the massacre, life in El Geneina came to a standstill, according to eyewitnesses and video from the ground. The city had fallen to the RSF and allied militias and the civil resistance by the non-Arab population had been vanquished.

“Bodies littered the street from Geneina Teaching Hospital all the way to the south of the city,” said resident Zahwi Idriss, who took video of that day.

“It was a ghost town,” he said. “There was nothing there except for corpses and horrific scenes.”

Clarification: This story has been updated to clarify the attribution related to the ICRC’s reporting of evidence in El Geneina.